The Risk Takers

Muslims who defied the Holocaust

Discover the story of ethnic Muslims in the heart of Europe who risked their lives to save their Jewish neighbors during the Holocaust.

IN PRODUCTION: The Risk Takers: Muslims who defied the Holocaust

Overview

What We Discovered

Jewish survival has a Muslim component.

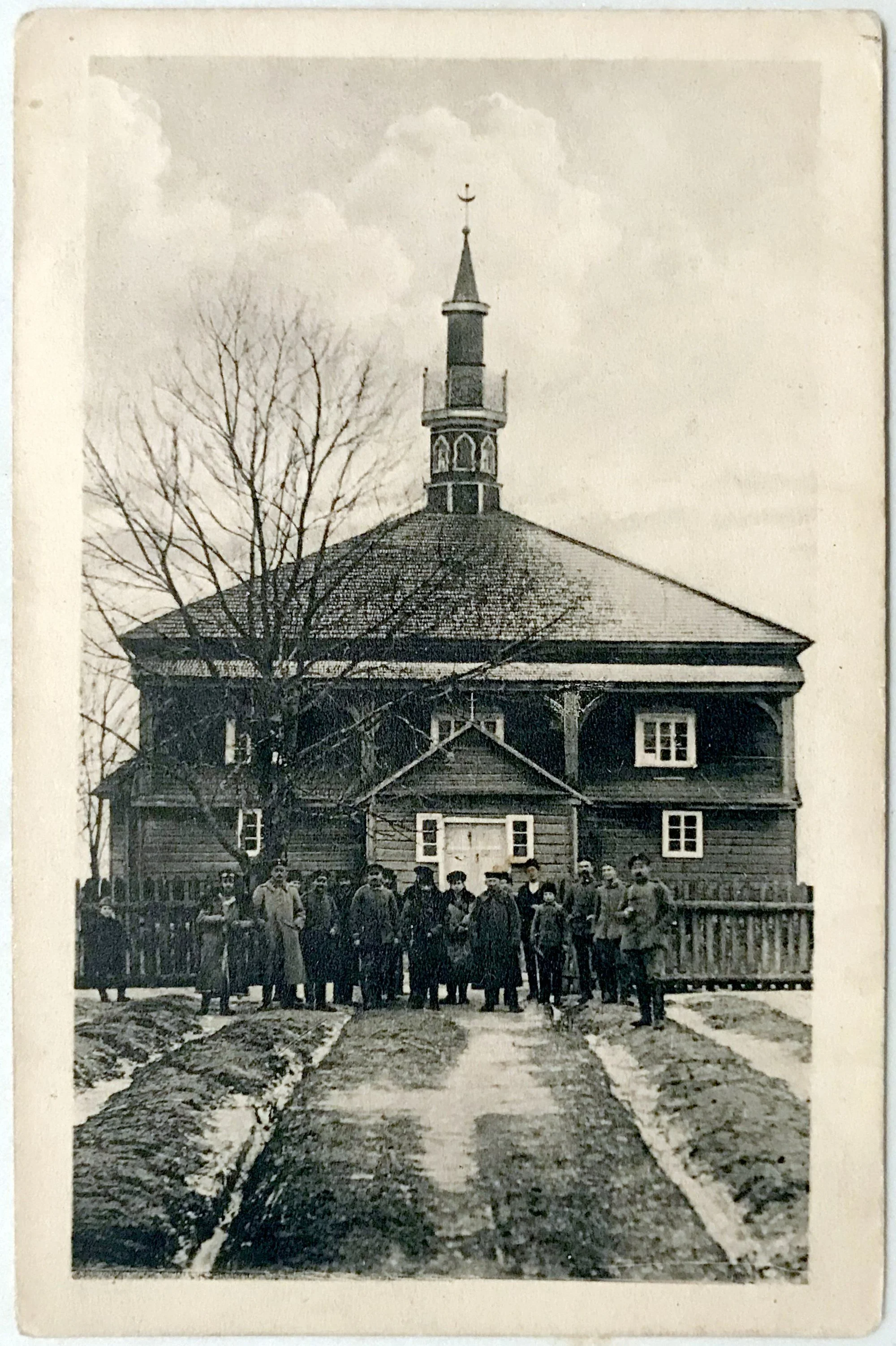

Tatar Muslims.

Descendants of Genghis Khan and the Golden Horde. A tiny group who have lived in Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, and Ukraine for centuries, individuals who deserve recognition for risking their own lives to rescue their Jewish neighbors during the Holocaust.

It’s an unknown story.

Until now.

THE MUSLIM RESCUERS

Almost 28,000 names are enshrined in the Garden of the Righteous Among the Nations at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, non-Jewish rescuers of Jews. But only two of those names - that’s right, only two - are Tatar Muslims.

We knew there should be more.

We found them.

In Kaunas, Lithuania, we discovered a “Muslim Oskar Schindler,” who, as a factory manager, used his facility to rescue Jews who lived in the nearby ghetto, including the baby of a Jewish couple.

“Schindler” (actually Matas Janusauskas) and his wife Tamara raised the Jewish child for two years before reuniting him with the parents when the war ended.

For our film, sitting in an unheated Lithuanian mosque last winter, we talked with “Schindler’s” nephew, an elderly member of the local Tatar Muslim community.

“I played with the baby,” recalled the man, now in his upper 80s.

“It was 1944.”

We crossed the border, to Gdańsk, Poland.

Again, in a mosque. Again, with a Tatar community member.

His grandfather had saved a Jewish woman and her two children.

When asked why, the now-grown-up grandson replied, “It was his human duty.”

TWO KINDS OF TRAILS

We drove the winding “Tatar Trail,” a road linking former shtetls where Muslims and Jews lived together. But there was also a paper trail, which helped us trace a half-dozen rescue stories for our documentary.

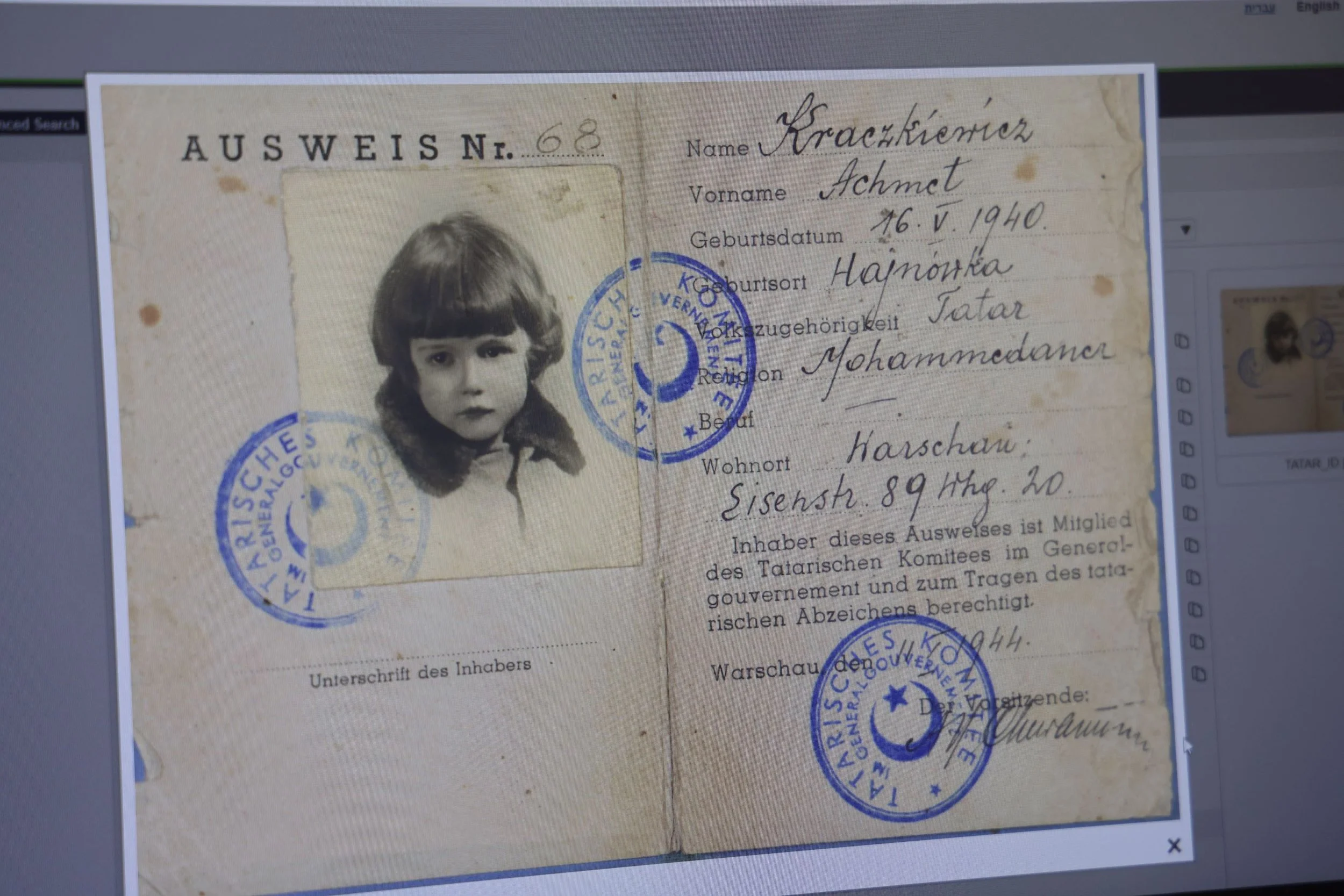

At the library in Yad Vashem, for example, we found phony documents declaring a Jewish boy in Warsaw to be a Tatar Muslim. Those documents, with the official stamp of the Tatar Community of Warsaw, helped the child survive the war.

But while documents “talk” in their own way, we also needed people who could talk, and even cry.

We learned of a Tatar Muslim rescuer in Ukraine, whose family hid a young Jewish man during the war.

The rescued man’s son now lives in Germany. The rescuer’s great-granddaughter lives in the United States.

As a direct result of our work, we reunited them (in Germany) and were there as they shared emotional stories of their families.

MORE THAN JUST A HISTORICAL FOOTNOTE

While these may seem like a series of unrelated events, we see them as completely related, which is part of our message. These sagas tell an overarching narrative of what it means to be a “risk taker” - then and now. One of our interviewees in Lithuania, who is Jewish, asked a key question: Would he risk his own life and the lives of his four children, in order to save a complete stranger. He wasn’t sure.

That was the crucial issue for every Holocaust rescuer, but in the case of Tatar Muslims, a minority of a minority, it may have been even tougher.

You’re already “different” from the majority. Do you just “go along,” or do you do what’s right?

What made some people answer the door, while others just heard the knock and did nothing?

We are not downplaying reality. There were Muslims, Tatars included, who either collaborated with the Nazis or did nothing, perhaps out of apathy, perhaps out of fear. We do not ignore that.

But it is also critical, with so much hatred in the world right now, to show that during a far worse reality - the Holocaust - many Jews and Muslims got along. Because they knew each other, they trusted each other. That is a lesson for today.

After traveling throughout the United States, Poland, Lithuania, Israel, and Germany we still kept going, for our final interview in, of all places, Hartford, CT.

The interviewee? The niece of the Jewish child who was saved by the “Muslim Schindler.”

The child’s name was Immanuel. He died several years after the war, his death unrelated to the Holocaust.

The name of the woman we spoke with?

Emanuella.

Named for the uncle she never met, who was saved by a Muslim couple who risked it all.

Emanuella was aware of part of the story, but as we told her what we had discovered, she learned something new about her Uncle Immanuel’s rescuers:

“I never knew they were Muslims.”

“Whoever saves a single life is considered by scripture to have saved the whole world.”

The Talmud, Sanhedrin 37a

“If anyone saved a life, it would be as if he saved the life of mankind.”

The Quran, Surah Al-Ma'idah (5:32)

Stories

-

“For them to agree to hide someone, they were really good, brave. They wanted to do something to help.”

During World War II in Ukraine, a Jewish teenage boy named Leonid Pilch—desperate and on the run—knocked on the door of a Tatar Muslim family he knew. The Nazis were closing in. The family did not hesitate: they sheltered him and helped him secure false identification papers.

Leonid survived. His son, Gennadiy—born after the war—became a musician and eventually made his home in Germany. In our film, Gennadiy returns to that history in an emotional meeting with a descendant of the very family that saved his father’s life.

Interviewed inside his home in Essen, Germany.

-

“I still get emotional when I talk about it.”

Nazly is the great-granddaughter of the Tatar Muslim family that sheltered Leonid Pilch, Gennadiy’s father, in Ukraine during the Holocaust. Today, she is an immigration lawyer in Cincinnati, Ohio—and an immigrant herself.

For Nazly, her family’s legacy of courage is more than history. It is a living guide. She says she is driven to help those considered “outsiders” or “different” because her ancestors once chose to protect a man who was both.

Interviewed inside her home in Cincinnati, Ohio and in Essen, Germany.

-

“I played with the baby.”

Ipolitas must be at least 85, but when he speaks, his memory is razor sharp—carrying him straight back to the chaos of World War II.

“I played with the baby,” he recalls.

The “baby” was Immanuel Grinberg, a Jewish toddler saved from certain death by Ipolitas’ uncle, Matas Janusauskas. Matas, a Tatar factory owner, became what some have called a “Muslim Schindler,” using his factory as a lifeline for Jews smuggled out of the Kaunas ghetto in Lithuania.

Those five simple words—I played with the baby—are not only a window into a moment of innocence amid horror, but also the kind of testimony that helps secure recognition as Righteous Among the Nations at Yad Vashem. Our documentary seeks to shine a light on the courage of Matas and his wife Tamara, whose bravery we believe is worthy of that honor.

Interviewed at the Raižiai mosque, about 15 miles from his home in Alytus, Lithuania.

-

“My brother survived the Holocaust because of Tatar Muslims.”

Yair never met his younger brother. Immanuel was a hidden child in wartime Lithuania, rescued by the “Muslim Schindler” of Kaunas and reunited with his parents after the war.

The family emigrated to Israel, but tragedy struck again: Immanuel died as a young child from an illness unrelated to the Holocaust, long before Yair was born.

Today, Yair is determined to honor the Tatar couple who risked their own lives to save Immanuel, keeping alive the story of the brother he never knew.

Interviewed at his home, outside Hartford, Connecticut.

-

“I never knew they were Muslims.”

Emanuella carries the name of her late uncle Immanuel—the hidden child rescued by the “Muslim Schindler,” Matas Janušauskas, and his wife Tamara. As Yair’s niece, she grew up knowing her family’s story of survival.

What she didn’t know—until we reached out during the making of this film—was that the rescuers who saved her uncle’s life were Tatar Muslims. That discovery gave her a new perspective, not only on her family’s history, but on the importance of remembering the unique bond between Tatars and Jews that made such rescues possible.

Interviewed at Yair’s home near Hartford, Connecticut.

-

“It’s their human duty.”

In a park in Gdańsk, Poland, a bronze Tatar soldier rides eternally on horseback, a sculpture honoring centuries of Tatar presence in the region. At its base is a poem—written by Selim Chazbijewicz, poet, Polish diplomat, and leader of the Tatar community.

When asked why his grandparents risked everything to save a Jewish woman and her two children during the Holocaust, Selim’s answer was as direct as it was profound: human duty.

Interviewed inside the Abrahama street mosque, Gdańsk, Poland.

-

“That’s why we call them silent heroes, because many were acting in secret. Many of them didn’t talk about what they did after the war. There are so many people waiting to be discovered.”

In many ways, Marta, is an ideal person for our film. A Holocaust scholar and curator of the Silent Heroes Memorial Center in Berlin, she has helped uncover some of those “many people waiting to be discovered.”

But that’s not all. Marta not only has the dedication of a historian, she also has a special connection to our saga. That’s because her family is Tatar Muslim on one side, and Jewish on the other. So for Marta, our documentary is not just history – it’s personal.

Interviewed at the Silent Heroes Memorial Center in Berlin.

-

“When the ghetto of Butrimonys was destroyed, two sisters were looking for a place—and nobody wanted them. My grandfather took them to his family from 1942 to 1944.”

Motiejus, head of the Union of Tatar Communities of Lithuania, is the grandson of a Tatar Muslim rescuer from Butrimonys, Lithuania.

The liquidation of the Butrimonys ghetto was a tragic story passed down in his family: children witnessing with their own eyes the destruction in the forest.

Motiejus’ grandfather–Jonas Radlinksas and his wife, Felicija Radlinskas– were at least able to rescue two Jewish girls.

Though the horror remained, so did their courage. The Radlinskas family saved lives—and were later enshrined at Yad Vashem, the only Tatar Muslims to receive that recognition. As our film shows, however, there are other Tatar Muslim heroes whose stories remain untold.

Interviewed at the Vilna Gaon museum in Vilnius, Lithuania.

-

“This is where my great grandfather helped Jews hide from the Nazis.”

Liucija, a University of Vilnius professor, guided us through Lithuania. She isn’t Muslim, but her family connections unlocked critical parts of our story.

In Kaunas, she pointed out a hospital her great-grandfather ran during the Holocaust, where he secretly sheltered Jews. Later, in Butrimonys, she led us to World War II-era census records—all in Russian. By chance, her Russian-speaking mother-in-law was with us. Flipping through the pages, she spotted the names of the two Jewish girls saved by the Radlinskas, the Tatar Muslim family later honored at Yad Vashem!

Interviewed in Kaunas, Vilnius, and multiple villages in Lithuania.

-

“She refused to tell me the entire story. I had to work on a project for high school about my family heritage.”

Liora is the daughter of Holocaust survivor Tsiporah Zhuravska Singer. Tsiporah grew up in the Polish shtetl of Iwje, where six members of her family were murdered and only two survived. Liora recounts, photo by photo, how and where each family member perished.

At first, like many survivors, Tsiporah would not speak of the horrors. Over time, she opened up—telling her children so they would remember and continue to tell the story.

Tsiporah was not rescued by a Muslim family, but many in her village were. Her life in Iwje helps illuminate the positive relations between Jews and Tatar Muslims in the interwar period, showing what life was like in a small, multicultural community.

Interviewed at Liora’s home in Jerusalem.

-

“When I was a kid, I thought that lox and bagels were Muslim food.”

Alyssa sits on the board of the oldest continually operating Muslim congregation in the United States—the Moslem Mosque, Inc. in Brooklyn, a Tatar mosque that still proudly uses the old spelling.

Her Tatar ancestors once lived in Polish shtetls side by side with Jews; Alyssa grew up as the only Muslim child in a Jewish neighborhood on Long Island. The context was different, but the closeness felt the same. She takes pride in the history of friendship between Tatars and Jews—whether in Eastern Europe or New York—and is determined to pass on that heritage to her own children.

Interviewed outside her home in Brooklyn, NY and at Ellis Island.

-

“For me, coping with [the Holocaust] has been a lifelong task. It took years for me to say my grandfather was a Nazi.”

Bettina, a research librarian at Yad Vashem, is not Jewish. Yet she has dedicated her life to Holocaust remembrance, in part to confront her grandfather’s Nazi past.

Her work was invaluable to our film. The records, documents, and photographs she helped us locate brought both victims and heroes back to life. Among them were forged papers that allowed a Jewish boy in the Warsaw Ghetto to pass as a Tatar Muslim child—and survive.

Interviewed at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem.

-

"To the right, you lived. To the left, you died. I watched my friend shot before my eyes."

Betty was only a child when she was smuggled out of the Kaunas (Kovno) ghetto. Her parents worked in a factory run by Matas Janusauskas, a Tatar Muslim who despised the Nazis. Behind the factory walls, he risked everything—sneaking food, passing whispers of escape, even saving lives.

Through his connections, Betty was hidden with a family from 1944 until the war’s end. She remembers her father lowering her into a sack and passing her over the ghetto wall—an act of desperate love. Her parents survived the camps. Her brother did not. Auschwitz claimed him.

Decades later, in Chicago, Betty recalls the terror, the loss, and the miracle of survival in an emotional interview for The Risk Takers.

Interviewed at Betty’s home in Chicago.

-

“For centuries, Jews and Christians clashed. But in the darkest moments, it was Muslims who often sheltered Jews—from the Crusades to the Inquisition.”

Ben, a Jewish college student and great-nephew of Holocaust survivor Tsiporah Singer, never met her. But his research into her hometown of Iwje uncovered a forgotten truth: in this small town, Tatars—Muslims—helped their Jewish neighbors survive.

Iwje was also the ancestral home of Alyssa, another voice in The Risk Takers. At Ellis Island, Ben and Alyssa trace their families’ immigrant journeys, discovering a shared past that carries a powerful lesson.

Despite today’s bitter conflicts, there was once a time when Jews and Muslims stood side by side. If it happened then… could it happen again? Ben reflects on this possibility—and its urgent relevance for our fractured world.

Interviewed at Ben’s mother’s home in Milwaukee.

Filmmakers

-

Jeff Hirsh

SENIOR WRITER & PRODUCER

As a broadcast journalist for 40 years in Cincinnati, Jeff won dozens of local, regional, and national awards. His documentary, “Finding Family,” followed a Holocaust hidden child back to Europe. The film was named Best Documentary in the U.S in 2003 by the Society of Professional Journalists, and was shown at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Jeff won 26 Regional Emmy Awards.

His series of reports, “Miss Katie’s Class,” followed a young Christian woman through her first year as a kindergarten teacher, at an Islamic day school. “Miss Katie’s Class” won an American Scene Award from the AFTRA broadcasting union, given for programming which highlights diversity.

Jeff has a BA in History from the University of Michigan, an MA in History from Washington University in St. Louis, and an MA in Journalism from the University of Missouri-Columbia.

Now retired from broadcasting, Jeff lives in Evanston, IL and works for the online newspaper “Evanston Now.”

-

Holly Huffnagle

LEAD RESEARCHER & PRODUCER

Holly is the author of “Peaceful Coexistence? Jewish and Muslim Neighbors on the Eve of the Holocaust” published in East European Jewish Affairs in 2015. She received her Master’s degree from Georgetown University focusing on 20th century Polish history and Jewish-Muslim relations before, during, and after the Holocaust. Holly lived and worked in Poland to conduct research on ethnic minority relations before World War II and was selected for the Auschwitz Jewish Center fellowship on pre-war Jewish life and the Holocaust in Poland and northern Slovakia. She has volunteered at the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum in Oświęcim and served as a liaison for the Jan Karski Educational Foundation, after graduating from Westmont College in Santa Barbara, CA with a B.A. in History.

Holly previously served the U.S. Department of State as a policy advisor to the Special Envoy to Monitor and Combat Antisemitism, and was a researcher at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in the Mandel Center of Advanced Holocaust Studies. She was also a Scholar-in-Residence at Oxford University with the Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy.

Today, Holly serves as the Director of Antisemitism Policy at American Jewish Committee, driving the organization's global approach to antisemitism policy, strategy, and prevention. (While Holly is employed by AJC, this film is not affiliated with AJC.) She lives in Washington, DC.

-

Chris Hursh

DIRECTOR & CINEMATOGRAPHER & PRODUCER

Chris is an award-winning photojournalist, video editor, and video producer, with 25+ years in broadcast journalism. He has won a national Emmy Award for Best Spot News in the United States, along with three Regional Emmy Awards and many other local, national, and regional honors.

Chris is the director of video production at Lakota School System in Ohio. Previously, he served as lead video strategist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, the #1 children’s hospital in the country (US News & World Report). He has produced dozens of videos, helping build the hospital’s worldwide reputation and attract 62 million visitors to its YouTube channel.

Previously, Chris spent 20 years in the television news industry. In addition to the many awards already noted, Chris has also freelanced for CBS News, NBC News, and other national and international outlets.

A graduate of Bowling Green State University, Chris co-founded a live, daily student-produced newscast which is now in its 29th year. Chris lives in Cincinnati.

For Educators

FORTHCOMING

Curriculum guides, lesson plans, and discussion materials to facilitate documentary use in schools, universities, and community groups.

Screenings

Coming in 2026!

☪️

✡️

Coming in 2026! ☪️ ✡️

Stay tuned for screenings

Gallery

Action

Join the campaign! Donate to support our film here.

Spread the word! Share The Risk Takers content on social media.

Subscribe below to receive The Risk Takers newsletter!